Pascal Pierme: Origines & Life

Thinking Through Form

Balance, energy, movement, interconnection, and nature are recurring themes in my work. I am interested in assimilating what is not supposed to fit, the combining of contrasting elements. I am creating an alphabet with which to speak my own language.

Pascal Piermé

Art Historian Robin Clark Essay (Reprinted with kind permission)

There can be no doubt that Pascal Piermé (b. 1962) is a formalist. Attention to the properties of his materials; a focus on balance, proportion, and texture in both two- and three-dimensional compositions; and refinement of technique and craft are all foregrounded in his oeuvre, which spans three decades. Piermé is largely self-taught, although he studied art practice and art history as a high school student and was exposed at an early age to the work of prominent modern artists including Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger, and Germaine Richier – whose influences were strongly felt in the French Riviera where Piermé was raised. He admits to being more attuned to nature than culture, and like artists ranging from Georgia O’Keeffe to Ken Price, has discovered a strong affinity for the landscape of New Mexico, where he has made his home since the late 1990s. (1) This does not mean, however, that his works are devoid of nuance, narrative, or ambiguity; rather, they demonstrate how Piermé thinks through form. (2)

Instead of taking a strictly chronological approach, this essay will consider the ways that fluid associations abound in Piermé’s work across time and media. In the case of the clustered totemic elements that are regularly occurring motifs in his sculptural production, the forms can be understood simultaneously as figurative and architectonic, with interpretations remaining open-ended. The five elements in Les sages 4 (2010) (fig. 1) could represent a community of elders or scholars, as the title implies, although the notches at their bases also suggest archways or portals. This double valence is more pronounced in a work such as Les citadines 1 (2019) (fig. 2). While the title (which may be translated generally as “city dwellers” or, in Piermé’s interpretation, as “women who live in town”) ascribes a degree of anthropomorphism to the work, the spire or steeple forms also suggest a cityscape.

Piermé’s engagement with the psychological and associative qualities of architecture is not limited to his sculpture. In 2009, he was awarded a three-month residency at the University of Xiamen on the southeast coast of China. (3) The program did not provide a workspace suitable for sculpting, so Piermé instead embarked on a series of watercolors using paper, ink, and paint discovered in the studio. (4) Regarding this body of work he explains, “I created 120 abstract watercolors very quickly, without any pressure on the results, and more than anything I fulfilled the need to create what being away from my studio and surrounded by new feelings brought forth.” The watercolors reveal a deft touch, an embrace of spontaneity, and a freshness born of simplicity. The series is titled Sapoe, and is named for the souvenir shop, or sapoe, that was located on the ground floor of the building where Piermé was staying at the time (he used the sapoe as a landmark when giving directions to taxi drivers, so wayfinding is a theme connected with this series). The composition of Sapoe 104 (2009) (fig. 3) is relatively loose; the shapes are created by allowing the thin watercolor washes to pool and bleed. Facility with the medium was necessary to guide the flow of the paint and particularly to control its boundaries, thus creating the rectangular negative spaces that remain raw paper in the center of each of the two bulbous painted forms. The white spaces resemble apertures or windows, conveying an architectonic association to something otherwise more akin to a cell dividing itself in two. This work may be inspired in part by Hungarian architect Antti Lovag’s Palais Bulles (Bubble House) (1989), a remarkable venue near Cannes. While living on site, Piermé assisted Lovag during the completion phase of construction of the complex and then managed Palais Bulles for its owner, Pierre Cardin, as an iconic location for fashion shoots during the early 1990s. (5)

Lovag employed spherical and ovoid modules as essential components of the chambers, windows, and doors of Palais Bulles, speculating that organic shapes are more habitable for humans than orthogonal ones because right angles are rarely found in nature (fig. 4). Bubble forms recur throughout Piermé’s watercolor series, including Sapoe 151 (2010) (fig. 5), which reads like the layout of a village. A strange spatial oscillation occurs in the work, in which some of the buildings seem to be presented in plan (as seen from above) and others in elevation (viewed head-on). The forms are more crisply realized and detailed than those in Sapoe 104. Here the window-like negative spaces have acquired panes or bars and the dwellings are inhabited by small red elements that seem to pulse with energy, animating the composition. This same energy form appears in Sapoe 150 (2010) (fig. 6), a work that features two different visual vocabularies and, like Sapoe 151, is equally convincing whether considered as a plan or an elevation view. At the bottom left corner of the drawing sheet are three dense passages of black pigment, one an anchoring block, roughly square, with two slender horizontal black elements floating closely above. Running through the black elements is a vertical zip of crimson. Piermé appears to have taken the wooden end of his paintbrush and gently dragged it through the red pigment from the bottom left corner of the sheet up toward the top right corner, where the composition shifts from an exploration of material density and affect to ethereal bubble shapes, the largest of which houses a crimson tablet. The thin red line traces the path of the energy, acting as a tether or umbilical cord linking the two aspects of the composition that otherwise occupy an expanse of blank white paper.

Architectonics emerge in diverse vocabularies throughout Piermé’s oeuvre. In a work such as Le village 10 (2015) (fig. 7), the relatively small scale of the elements (each one is about twelve inches tall) creates a sense of intimacy, and the hidden spaces in the folds of the forms suggest interior and private chambers. Like most of Piermé’s sculptures, this piece is made from mahogany, a material he favors for its resistance to cracking, minimal grain pattern, and availability in larger dimensions than other types of wood. (6) Each of the works in this series represents a row of small dwellings with both ancient and futuristic overtones. Some reveal the natural brown tones of mahogany, while others, such as Le village 5 (2013) (fig. 8) have been stained yellow, lending them more of a Pop Art quality, although the grain of the wood still shows through. Other works, such as Ensemble 5 (2008) (fig. 9), seem to take their construction as their theme, so that the assembly of the parts is one potential outcome while other results or reassemblies remain possible. Piermé has said, “I am not trying to conclude or explain anything in a piece; rather, I am inviting viewers to take their own internal journey of discovery with me.”

While Piermé’s body of work is rife with architectural references, it also includes works situated in the realm of biomorphic abstraction. For example, the shape and dull gleam of Sleeping Violin (2001) (fig. 10) evoke a beetle’s carapace when seen from above, or a pincer when viewed from the side. To achieve the compelling surface quality of this work, after hand carving the form, Piermé burned the mahogany black with a torch and then burnished it with wax. The last in a long series of related works, Sleeping Violin was originally installed supine, or as he describes it, “at rest,” although it is presently hanging vertically on a wall in Piermé’s home. While it may seem counter-intuitive to lean into a fauna-based interpretation of this work when the title clearly references a musical instrument, Piermé’s attitude toward his titles is that they “merely serve as portals of entry for the imagination” and for some viewers at least the animal-world association with this work is strong. Similarly, a sculpture such as Generation 5 (2013) (fig. 11), with its interlocking petal forms, references the plant kingdom, as do the acorn cap-shaped elements of Sapoe 20 (2009) (fig. 12).

Questions of scale and fabrication methods are inherent to the field of sculpture, and Piermé has given a great deal of thought to them. Shifts in scale and materials offer different kinds of engagement, as is visible in the comparison of Confidence and its maquette (fig. 13). The intimate scale and warmth of the wooden maquette draws a viewer in, while the more imposing size and industrial surface treatment of Confidence makes a more assertive statement. On this topic, Piermé says, “With a smaller sculpture I feel that I want the viewers to come to me. With a larger sculpture, the opposite is the case.” When working on a maquette for a larger work, Piermé tries to imagine either that the model is at the final size of the complete work, or that he himself is small in relation to the model. “It is a very intimate feeling,” he explains, “like creating a seed or an egg, something that will evolve.”

When it comes to making the wood sculptures, Piermé avoids working with assistants, preferring to undertake all aspects of production himself. “I believe in a creative relationship to the whole evolution of a piece from A to Z, including purchasing the materials and wrapping the work when it is ready to be shipped.” On the other hand, he does work with fabricators to create his metal sculptures, making a wooden maquette to be scaled up in steel. “The fabricator builds the work in steel and I do the finish,” he explains. “I use a fabricator because my studio is not designed for working with metal, and because the steel pieces are always editioned works and I don’t see myself making the same piece repeatedly.”

As previously mentioned, Piermé has a strong affinity for the properties of mahogany, which he has described as a “wise and noble” wood. This is particularly apparent in works such as L’esprit (2015) (fig.14), in which he embraced the damage and imperfections inherent in the wood that had been left outdoors and exposed to the elements before he acquired it. He polished one side to reveal the original color and pattern of the wood, while leaving the other side in its grey, weathered and cracked state, creating an elegant contrast. Other than cutting and fitting two pieces of the wood together, Piermé’s manipulation of it was restrained, allowing the inherent materiality of the work to constitute its meaning.

As opposed to the minimal approach he took for a work such as L’esprit, there are times when Piermé elaborately fashions numerous elements before bringing them together to produce a single work. This accumulative method is popular with modern and contemporary sculptors ranging from El Anatsui, who creates exuberant tapestries from recycled foil bottle tops stitched together with wire, to Wolfgang Laib, who collects pollen he then painstakingly sifts into vibrant fields of color directly onto gallery floors. Piermé cites as early influences the assemblage artists Arman (whose sculptures often took the form of found objects suspended in blocks of transparent polyester resin) and Louise Nevelson (who collected wood scraps and adhered them together to create monumental wall sculptures). One of Piermé’s most expansive series, Les Origines, employs an accumulative technique, although the elements are handcrafted by him rather than the industrial or organic “found” materials employed variously by the aforementioned artists. For example, Petites Les Origines 18 (2018) (fig. 15) comprises twenty pieces of cut, carved, sanded, stained, and painted walnut. The wall-mounted array measures 26 x 40 inches in perimeter and is several inches deep. Depth is important here because some elements are notched on verso, creating intriguing and dynamic patterns as a viewer moves around the work. Piermé notes that although wood is an unforgiving medium that does not easily allow for spontaneity, in the Origines series he has found a method that allows for improvisation in the combining and recombining of elements. Other examples from the Origines series involve a geometric shape painted so that it appears projected onto the assembly of vertical wooden elements, creating a lenticular effect. Origines Temporelles 21 (2019) (fig. 16) is a roughly square composition comprising sixteen pieces of stained and carved mahogany over which a light blue trapezoidal shape has been painted. Approached straight on, the painted image appears ghostly and dispersed, diluted by the white negative space between each of the wooden elements. A raking view from right to left reveals the image as bold but fragmented, the blue paint contrasting strongly with the darker brown wood and the negative white space minimized. A raking view from the opposite direction causes the painted image to appear continuous because on this side Piermé has painted not only the tops of the sticks but also their sides. Such a work foregrounds the perception and mobility of the viewer and integrates itself into its architectural surroundings.

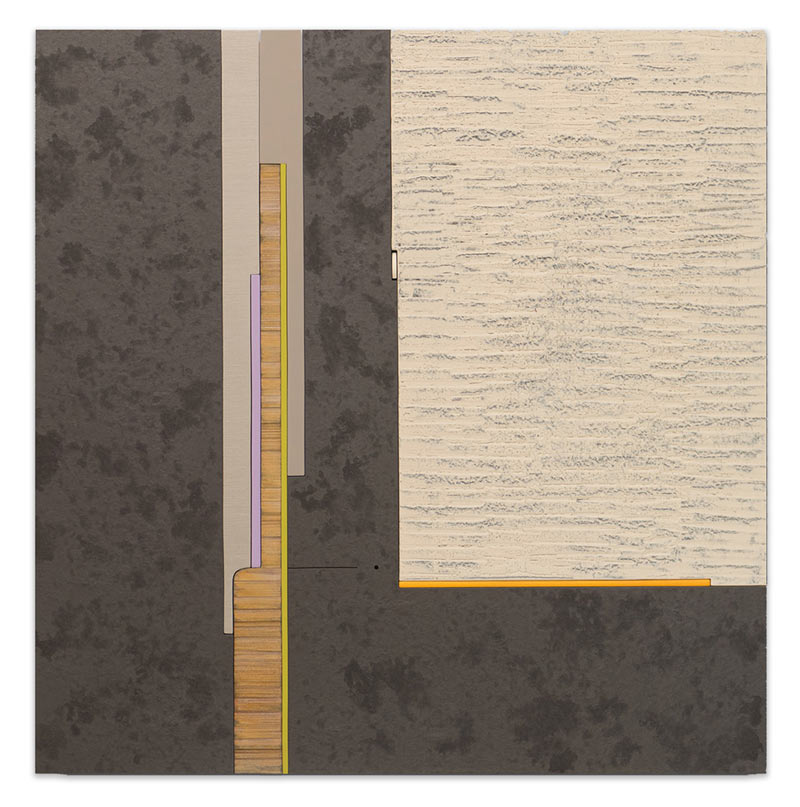

At this point it is worth noting Piermé’s approach to color. Much of his palette is earth-toned, in harmony with the medium of wood and the high-desert landscape where he lives and works (fig. 17). On occasion, however, he will pivot to the use of vibrant hues including cadmium orange as a powerful accent in otherwise dissimilar works such as Les Origines 73 (2021) (fig. 18) and Je Suis 1 (2012) (fig. 19). The predominant tones in Les Origines 73 are neutral: grey, black, and cream. The elements are notched not only from behind, as is common in this series, but also on the sides, which gives the sense that they are somehow being presented in profile and encourages the viewer to move around to see them from the side. Bold strokes of orange inhabit most of the notches, lending the work a complexity that underscores how differently things appear depending upon one’s point of view. Orange is also deployed strategically to lead the eye around Je Suis I, a work in which two chunks of mahogany have been sutured together with a deft bit of wood joinery of the sort more commonly used by furniture makers than sculptors. The overall shape of the piece is square, with notches cut from each of the four sides, and a small rectangular aperture hovers just above the center. The notches and aperture are coated in orange pigment, while the rest of the work is whitewashed. These orange accents emphasize the contours of the piece as well as its objecthood.

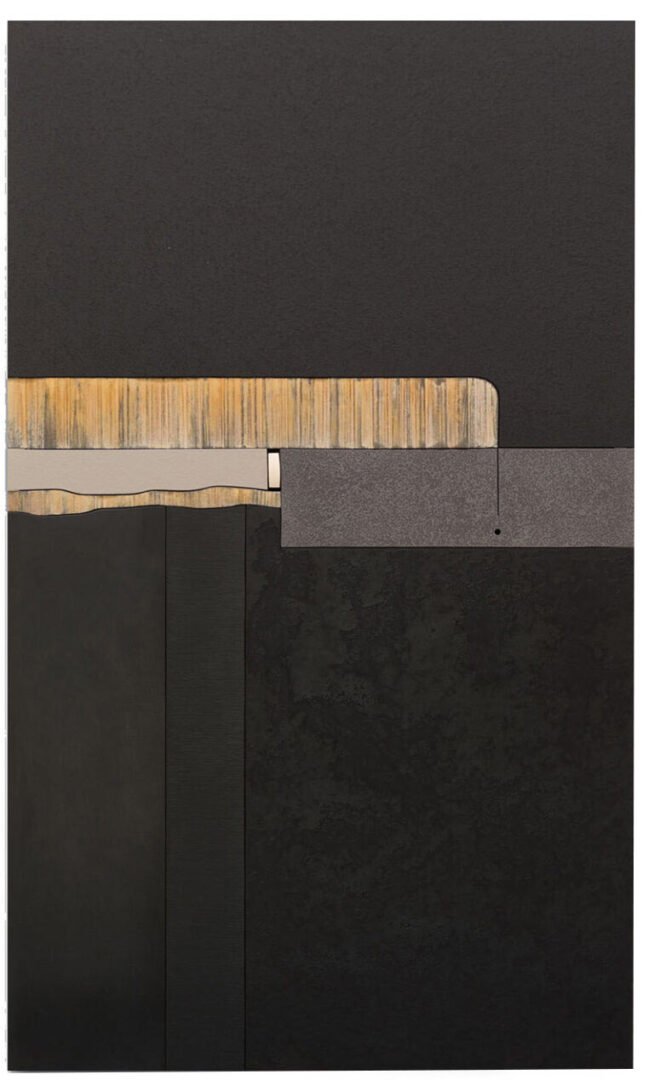

Opposite to his approach of using bright pops of color to lead the eye, Piermé will sometimes opt to unify the elements of a sculpture or relief with a monochromatic application of paint. A key example of this is Noir on Me 21 (2021) (fig. 20). Works in this series begin with a drawing, which is often an amalgam of imagery inspired by satellite photography and Piermé’s perceptions of the local landscape. Continuing the technique developed in the Sapoe drawings of combining plan and elevation views to develop spatial tension, these study drawings include aerial imagery (in which the undulations of the earth’s surface are defamiliarized due to an extreme shift in scale) as well as visual elements gleaned at ground level while hiking in the desert. The drawing then serves as a template from which Piermé cuts a panel of compacted wood into pieces. Each piece is individually treated with glossy or matte paint and patinas, then reassembled to create a raised topography. Inserted into Noir on Me 21’s dark expanse are two small nubs of holly — a hard, white, close-grained wood typically used for inlaid marquetry. Holly carries with it strong associations in both Christian traditions and pagan folklore, although in this work its material properties are foregrounded. Chosen for its density and for the stability of its naturally pale hue, the smooth holly contrasts vividly with the dark expanse of collaged and treated wood, like beach pebbles bespeckling a black lava field.

As we’ve seen, Piermé’s practice is both empirical and intuitive, exploring fluid associations between the natural world and the built environment. It is an experimental and organic approach in which one exploration leads to the next. No line of inquiry is really abandoned, only adapted to a new situation. Just as authors tend to develop their ideas through the process of writing, so Pascal Piermé thinks through the manipulation of form.

Robin Clark

1 – All quotes and biographical information in this essay were gathered during conversations with the artist in May, June, and July of 2021.

2 – The notion that “making is a form of thinking” is inspired by Glenn Adamson and Julia Bryan-Wilson’s book, Art in the Making: Artists and their Materials, from the Studio to Crowdsourcing (London: Thames and Hudson, 2016), p. 19.

3 – The residency was administered by the Chinese European Art Center (CEAC) which was founded in 1999 by the Dutch philanthropist Ineke Gudmundsson. The mission of the program is to encourage cultural exchange between Europe and China.

4 – During this residency Piermé also collaborated with a traditional porcelain studio to produce an editioned sculpture entitled Mitox (2009) inspired by the concept of a “feeling Buddha.”

5 – Cardin commissioned a sculpture by Piermé for the entrance of Palais Bulles. The work, Reincarnation 1, 1994, measured about 22 inches in diameter and was carved in Siporex, a concrete material. Piermé explains, “The sculpture is that of a man ‘bubbled’ in a sphere, in fetal position as a symbol of rebirth, resulting in a new generation – a new man. The sphere is symbolic of protection and it gives the feeling of whether or not the man desires to emerge or remain.”

6 – Piermé occasionally works with other types of wood including walnut and aspen. He notes that all the wood he uses is approved by the Forestry Stewardship Council, ensuring that it has been sustainably harvested.