An interview by Katherine Williams, curator and Josh Ryders, curator landescape@europe.com

1) Hello Pascal and welcome to LandEscape: you are an established artist, yet at a young age you gained a reputation as a promising European young sculptor. Are there any experiences that particularly directed the trajectory of your art work? Moreover, how did your previous collaborative projects alongside creative giants such as Pierre Cardin inform your cultural substratum and influence your evolution as an artist?

Meeting my biological father, who is an artist, when I was 18 years old was the seed of my artistic career. At that time, I had no idea that I would become an artist, but I was certain that I would be creative with my hands. I was blown away by the freedom of the artistic lifestyle, especially coming from dental technician school where rigor and regulations were so prevalent and important. It was a breath of fresh air. Yet I had the notion that the artistic life included inherent accepted public behavior – playing certain games and displaying attitude – and these were not part of my character, I had no intention of engaging in that. When I plunged into the artistic world, my trajectory was clear from the beginning: be in the studio, have fun and be honest with myself. All the rest had to follow and adapt to these concepts. The best experience I had, and still have, is to observe, listen and learn quietly from creative people: those who are successful and well-known, but also from others who have not been that successful or prominent. I liken it to driving: it is dangerous to stay too close to the car in front of you, keeping a bit of distance and having patience is the best way to have a real overview. And this is the best way for me to learn.

Working for Mr. Pierre Cardin in a very privileged position over 4 years was one of the most magnificent experiences in my early career and I still measure the impact of it today. Many times I had the chance to share lunch with him, just the two of us. I had in front me a “giant” of creativity, as you said, who had no filter and would talk about any subject with me. I was totally impressed by the way he could handle so many endeavors at the same time and yet would still be so thirsty for more creativity. He once said “Something finished is something dead. It’s not about the death of a project that is the most interesting, but more about the necessity to begin another one immediately.”

One project I worked on with him was a 50-foot high sculpture made out of tubes, laser and water. The sculpture was supposed to be installed on top of a theater that Mr. Cardin owned at the Palais Bulles in Théoule-sur-Mer. It was intended to be like a lighthouse. He wanted people from as far as Cannes to be able to see it. Unfortunately, the project was rejected and only existed in our minds. After that he commissioned me to do a sculpture I called “Reincarnation.” This piece is still on display in the main entrance at the Palais Bulles.

When working on a creative collaborative project, 50/50 does not work very well. Usually, it is more about how to fit two 100 percents together. The only way, what is the most constructive experience, is that both artists have to compromise – this is usually impossible, but when it works it is wonderful. Excellent communication helps to define the rules and it assists in accepting differences between the collaborators.

Working on a project with Mr. Cardin was not this kind of situation, of course. It was more about me existing as a little flower near a sequoia, and it worked very well. Learning, learning and more learning mattered. Being humble is a big plus; too large an ego build barriers and stops the honest and kind transfer of information. Accepting the idea that you do not know things helps you to absorb, digest and redefine your way.

2) Rejecting any conventional classification, your works convey freedom and a rigorous approach to geometry. Before starting to elaborate about your production, we would suggest that our readers visit https://pascalpierme.com in order to get a synoptic view of your work. In the meantime, would you like to tell our readers something about your process and set up?

My studio is roughly 250 sq m (2700 sq ft) consisting of two very distinctive rooms with high ceilings. The first room is for clean work, the other one for dusty, grittier work: wood cutting and carving. The need for two separate spaces was a true technical problem until I was finally able to design my own studio near my home.

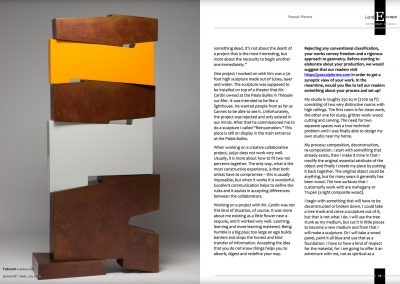

My process: composition, deconstruction, re-composition. I start with something that already exists, then I make it mine in that I modify the original essential attribute of the object and finally I create my piece by putting it back together. The original object could be anything, but for many years it generally has been wood. The two surfaces that I customarily work with are mahogany or Trupan (a light composite wood).

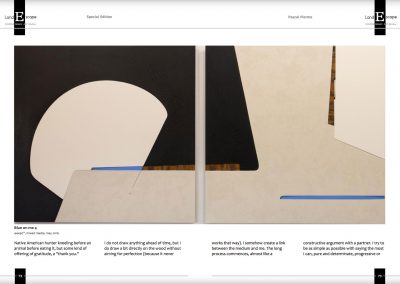

I begin with something that will have to be deconstructed or broken down. I could take a tree trunk and carve a sculpture out of it, but that is not what I do. I will use the tree trunk as my medium, but cut it in little pieces to become a new medium and from that I will make a sculpture. Or I will take a wood panel, paint it all blue and use that as a foundation. I have to have a kind of respect for the material, for I am going to offer it an adventure with me, not as spiritual as a Native American hunter kneeling before an animal before eating it, but some kind of offering of gratitude, a “thank you.”

I do not draw anything ahead of time, but I do draw a bit directly on the wood without aiming for perfection (because it never works that way). I somehow create a link between the medium and me. The long process commences, almost like a constructive argument with a partner. I try to be as simple as possible with saying the most I can, pure and determinate, progressive or safe. It all depends how I feel that day. When the drawing is finished I know I will not go back to it; it is never an option. I prefer to go right to the wall or to pick an elaborate detour to satisfy my need, but I will not go back.

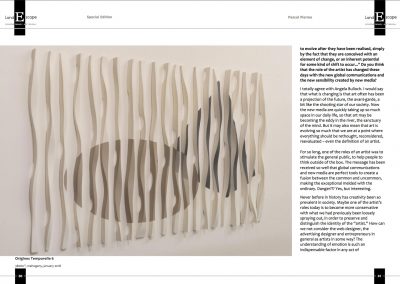

Now it is time for the cutting and deconstruction. In the dusty area of my studio, using simple tools, I cut the wood in pieces following the trace of the original drawing. As with a puzzle, I put those pieces back together on a background. This process is not what I would call “creative time.” It is more preparatory work and focus on making those cuts as precise as I can. Now that I have my parts cut out, it is time to decide if I want to reshape some of them, where to create texture and the colors and patina options.

As do many artists, I would say that I create as I feel, but I often underestimate the opposite. With that I mean creating as I would like to feel. It is the difference between saying you could take a walk in nature because you feel like it or because you have the need to feel the walk. It is almost the same, but not exactly. After all the pieces are sanded and sprayed, after each has been marked with the colors/texture/patina information needed for the rest of the process, I bring all those pieces into the clean room of the studio. I display them in different areas for each different preparation of the final aspect. I work flat on tables to paint, spray, brush, varnish, wax, burn, etc. When all the pieces are dry and ready to be put back together on the background, it is always an initial emotional moment. This is when I am happy or not, when the message is there or not, when I feel proud or disappointed. But I remind myself that this is a flat view and I need to wait to have the final real vision of it. It is only when all the pieces are screwed on from the back that I can see the piece on the wall – this moment is the moment of truth.

When I work on wall pieces, pieces that I mainly call “origines,” the process is different, but the beginning technique is the same – cutting sticks of wood individually and recreating a piece by regrouping.

3) The body of work that we have selected for this special edition of LandEscape has caught our attention in the way that you provide the visual results of your analysis with autonomous aesthetics: we have really appreciated the vibrancy of thoughtful nuances that saturate your artworks and especially the way they suggest the idea of plasticity. Is there any specific material you would like to talk about that could show us how you choose the material for a piece?

In the ‘90s, I turned some of my wood and plaster sculptures into bronze. I discovered that bronze was not necessarily making the sculptures better. This meant to me that material has a very important impact on the art work. It also meant that every sculpture calls for the best material for it individually, but the question is which one? Instead of approaching the subject on an intellectual level, I discovered that the most harmonious material turned out to be a logical choice. I always believed that painters are much more intellectual than sculptors, who have a casual approach to the subject, a more grounded resonance. Since wood is my favorite, I had to accept that the way to select my material was to utilize the medium that most suited the end goal of executing my concepts.

4) Investigating the tension between the physical and the abstract, your artworks provide tactility and elusive notions of the imagination: would you say that the way you provide the transient with a sense of permanence allows you to create materiality of the immaterial?

Yes, I do. A few years ago, I wondered if I could paint only, doing a similar wall piece on a canvas without having to cut any wood, sanding anything or reshaping any surface – the result was totally different. I really believe that I talk about, think about, and approach my work with a 3D mind; this has a huge impact on the final interpretation. It is like having an accent when you talk or a scar on your skin – it is always there.

Another metaphor would be to compare a movie and a live play. Staging a live play would be much harder, but maybe more realistic in some way. So as in my work, the separation of two colors is different if a cut is placed between them; the cut is as important as the color differences. The material is a tactile statement of an abstract message. This is contradictory, but significant, in my work.

5) British multidisciplinary artist Angela Bulloch once stated “that works of arts often continue to evolve after they have been realised, simply by the fact that they are conceived with an element of change, or an inherent potential for some kind of shift to occur…” Do you think that the role of the artist has changed these days with the new global communications and the new sensibility created by new media?

I totally agree with Angela Bulloch. I would say that what is changing is that art often has been a projection of the future, the avant-garde, a bit like the shooting star of our society. Now the new media are quickly taking up so much space in our daily life, so that art may be becoming the eddy in the river, the sanctuary of the mind. But it may also mean that art is evolving so much that we are at a point where everything should be rethought, reconsidered, reevaluated – even the definition of an artist.

For so long, one of the roles of an artist was to stimulate the general public, to help people to think outside of the box. The message has been received so well that global communications and new media are perfect tools to create a fusion between the common and uncommon, making the exceptional melded with the ordinary. Danger??? Yes, but interesting.

Never before in history has creativity been so prevalent in society. Maybe one of the artist’s roles today is to become more conservative with what we had previously been loosely spraying out, in order to preserve and distinguish the identity of the “artist.” How can we not consider the web designer, the advertising designer and entrepreneurs in general as artists in some way? The understanding of emotion is such an indispensable factor in any act of constructiveness. Speed, fast speed, is pushing us to constant reinvention. Creativity’s sparkles handed forth by the influence of generations of artists is now speaking to and through everyone… an indispensable tool.

6) How do you go about naming your artworks? In particular, is important for you to tell something that might walk the viewers through their visual experience?

I personally do not have any rules concerning titling my work. Sometimes I name my work according to the piece and give it a title that will, as you say, “walk the viewers” a bit; sometimes it is just a personal reference; and sometimes it is totally private and very personal, given form by the experience during the construction process. Giving minimal information in the title is preferable to me; I believe more in the artist’s statement for a show then the title of a piece. For example, asking the name of a person I want to talk with would not be my first question. It may influence me when the person starts speaking and I prefer to have a totally free, uninformed first feeling.

7) As you have remarked once, you try to sculpt in a way that allows you to change your mind until the last minute: how important are play, spontaneity and improvisation in your approach? In particular, do you conceive your works instinctively or do you methodically elaborate your pieces?

That is the trick for me. Because I am using a sculptor’s approach for flat surfaces, I have to integrate spontaneity and specific methods in a certain order. I sincerely believe that for an artist to be creative he has to surprise himself during the process. Building a piece that has been preconceived could end up being too much of a controlled process. Now, the “spontaneous, creative” moment might only be a few seconds and still have a major role – it is what is going on with my work. At first, it was a natural approach, then it became a necessity and even a vital point. For me, being able to change my mind at any moment, as a painter can do, is not possible. As I progress, the point of no return is more frequent. I start on a large open field and end up having to go through a little door. I have to accept that and since I know that, the little narrow door itself becomes an opening to a new large open field.

8) The power of visual arts in the contemporary age is enormous; at the same time, the role of the viewer’s disposition and attitude is equally important. Both our minds and our bodies need to actively participate in the experience of contemplating a piece of art: it demands total attention and a particular kind of effort – it is almost a commitment. So before leaving this conversation, we would like to pose a question about the nature of the relationship of your art with your audience. What do you think about the role of the viewer? Are you particularly interested in trying to trigger the viewers’ perception as a starting point in order to urge them to experience personal interpretations?

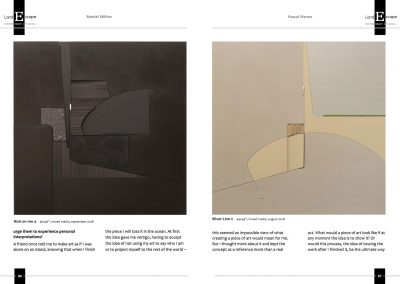

A friend once told me to make art as if I was alone on an island, knowing that when I finish the piece I will toss it in the ocean. At first the idea gave me vertigo, having to accept the idea of not using my art to say who I am or to project myself to the rest of the world – this seemed an impossible view of what creating a piece of art would mean for me. But I thought more about it and kept the concept as a reference more than a real act. What would a piece of art look like if at any moment the idea is to show it? Or would this process, the idea of tossing the work after I finished it, be the ultimate way to see what is inside of me and wants to come out? Another question came to me…if it is only for me, why should I do it? Maybe meditation or just a walk in the public park is art for yourself, no need of materialization. I think there are as many answers to that as there are artists; everyone has a personal thought about the subject.

After 30 years of juggling in my studio with colors, pieces of wood, emotions, technicalities, art business and galleries, how could I ignore that the viewers are very important to me and that I will always need, in one way or another, a kind of fusion with the viewers. If I had a clear message I would need the viewers to understand my work, but I do not want clear messages. I assimilate my work as text in an alphabet puzzle, then the viewer will see a novel, a poem or a word. The viewer is often interpreted as a person, a sensitive being, a collector, an art critic, a friend, etc. But to me it could be a mass of people. Can you imagine the Rolling Stones playing for one person? The Pope at the Vatican window with one spectator? No. Would the Pope’s message or the Stones music be the same if they knew that it would be only one person there? Probably not. I feel the same way. I sense a larger timeless audience rather than a single viewer.

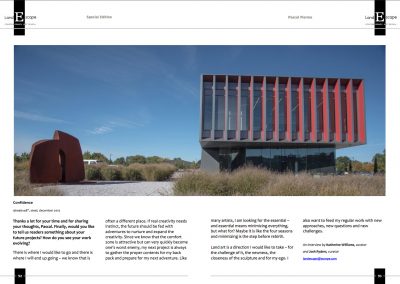

9) Thanks a lot for your time and for sharing your thoughts, Pascal. Finally, would you like to tell us readers something about your future projects? How do you see your work evolving?

There is where I would like to go and there is where I will end up going – we know that is often a different place. If real creativity needs instinct, the future should be fed with adventures to nurture and expand the creativity. Since we know that the comfort zone is attractive but can very quickly become one’s worst enemy, my next project is always to gather the proper contents for my back pack and prepare for my next adventure. Like many artists, I am looking for the essential – and essential means minimizing everything, but what for? Maybe it is like the four seasons and minimizing is the step before rebirth.

Land art is a direction I would like to take – for the challenge of it, the newness, the closeness of the sculpture and for my ego. I also want to feed my regular work with new approaches, new questions and new challenges.